BSPD Presidents Blog 19th January 2026

Nineteen Weeks In - and Building Real Momentum

(Twenty by the time you read this…)

As I write this, we are just over 19 weeks into my presidency — and by the time this blog is published, we will be approaching the 20-week mark. It feels like the right moment to pause and reflect, not because I have managed to find a couple of moments to breathe and slow down, but because the past few months have been exceptionally busy, deeply collaborative, genuinely productive and thoroughly enjoyable!

Chairing my first Executive Committee meeting was truly a baptism by fire—it was both wide-ranging and demanding. However, what has been most encouraging are the developments since then: ongoing conversations, new connections, and steady progress across the Society and beyond.

Working across networks and nations

A significant focus over recent months has been supporting colleagues working to strengthen Clinical Excellence Networks (CEN) in Scotland, particularly where formal Managed Clinical Networks (MCN) (the preferred model used in England) are not yet funded. I have met with colleagues from the West of Scotland BSPD branch, who are leading thoughtful, proactive work in this area. Their upcoming national networking event on 7th February will bring together key stakeholders from across Scotland, and I have been working closely with Fran O’Leary and Christine Park to explore how BSPD can support and amplify the outcomes of this event.

What has been particularly important in these discussions is the recognition that challenges around service provision, access, and equity are not confined to a single system or nation. We have agreed to reconvene after the event to consider the next steps, including engagement with Chief Dental Officers across the devolved nations, ensuring learnings are shared, and momentum is ensured.

Alongside this, there has been sustained and important work in collaboration with CLAPA on the “Cleft Dental Crisis”. I have been working closely with the Paediatric, Restorative, and Orthodontic Cleft CENs to lead this work on behalf of the Society. This collaborative approach — across multiple specialties — is essential if we are to support children and families effectively.

National conversations and advocacy

In December, I attended the All-Party Parliamentary Group (APPG) Christmas reception at the House of Commons, hosted by the British Dental Association (BDA). Hearing national perspectives on oral health from Members of Parliament, including Minister Stephen Kinnock, reinforced how visible — and how urgent — children’s oral health has become within wider policy discussions.

It was also a valuable opportunity to represent BSPD at a senior level, engage with the Chief Dental Officer for England, Jason Wong, and hold meaningful conversations with professional leaders. I was particularly pleased to discuss Child Focused Dental Practices with Shiv Pabary, Chair of the BDA’s General Dental Practice Committee, and to share learning from this work.

Education, outreach and growing engagement

Member engagement has been a real highlight of this period. In December, I spoke at a Pan-London DCP Study Day at the Eastman on the development of Mini Mouth Care Matters (Mini MCM) and routes for involvement. BSPD hosted a trade stand, supported by colleagues from the South-East Branch, creating space for conversations with allied dental professionals and potential new members. We were also able to distribute toothbrushes and toothpaste thanks to the generous support of Henry Schein.

Delivering my first Presidential Address to the South-East Branch shortly afterwards was a particularly special moment. The feedback was overwhelmingly positive, with members valuing both the honesty about the challenges we face, and the focus on what we can achieve together.

I was also delighted by the response from the wider membership, with a record 50+ expressions of interest to contribute to the BSPD–RCPCH Oral Health Integration Toolkit, and many members at all stages of their careers, keen to be involved in the development of the updated clinical standards. A working group is now established for the toolkit, and the standards group continues to take shape. This level of engagement so early in my term has been genuinely humbling. This is exactly how we should be operating as a Society.

Clinical standards, workforce and communications

Work on the revision of the Clinical Standard for Paediatric Dentistry has continued at pace whilst establishing the core working group, including a second Project Board meeting with the Office of the Chief Dental Officer, England, and the National Commissioning Team. A key step forward has been agreement to reframe the document to reflect a broader focus on Children’s Oral Health, recognising the vital contribution of allied healthcare professionals across primary, secondary and tertiary care.

We have finished interviews for the Special Advisor role following an open recruitment process that attracted a large number of applications. We were impressed by both the quality and quantity of candidates. I am pleased to announce the appointment of Claire Stevens to the position of Special Advisor. In addition, we have started discussing how our media and PR functions should adapt to support the increasing scale and complexity of BSPD’s work. I am also happy to report that Kate Clark has been promoted to Director of Communications for the Society—an obvious next step as we continue to grow and reach a broader audience. We are also supported in the Media Team by our group of trained Media Spokespeople and our Social Media Consultant, Angela Otterson.

Digital infrastructure and shared resources

As the new year began, attention turned to some of the practical foundations that underpin all of this activity. We have revisited BSPD’s support arrangements with the Royal College, reviewed our Memorandum of Understanding, and begun taking a more strategic look at how the BSPD website can support an increasing volume of high-quality resources.

There is strong shared ambition to host and signpost selected outputs from our oncology, cardiology and cleft CENs via the BSPD website. This is complex work, and a dedicated meeting with the relevant CEN Chairs will work to ensure governance and feasibility.

Progress has also begun on a BSPD led oncology oral health video, led by Claudia Heggie. The script is in draft format, production is underway, and discussions are ongoing with CCLG about potential collaboration, recognising the shared audience and impact of this work. We are grateful to The Christie who have agreed to part-fund this resource.

Inclusion, additional needs and system leadership

Finally, I have been grateful for the opportunity to engage with colleagues at SeeAbility exploring how learning from children’s dentistry within community services might inform eye-care commissioning for people with additional needs. These discussions sit squarely within the ambitions of the NHS 10-Year Plan, including sensory checks and provision within special educational settings, and we will continue to explore BSPD’s role as this work develops.

Looking ahead

Twenty weeks into my term of office, the pace has been intense — but what stands out is the collective commitment across the Society. From CENs and policy partners, to trainees, allied professionals and consultants. BSPD’s strength continues to come from its members.

Thank you for your engagement, your ideas, and your willingness to contribute. If anything in our recent work — or in the Presidential Address — have sparked interest, please do get in touch. BSPD exists because of you, and I look forward to continuing this journey together.

Photo 1: APPG Christmas reception at the House of Commons (Eddie Crouch, BDA Chair & Jason Wong, CDO England)

Photo 2: Pan-London DCP Study Day, Eastman Dental Education Centre, UCLH, London

Photo 3: An exceptional turn out (46 members) for the joint East and West of Scotland Presidential Address

Reflections from My First Seven Weeks as BSPD President: A Journey of Connection, Collaboration and Commitment

By Dr Urshla (Oosh) Devalia, President, British Society of Paediatric Dentistry

November 2025

A Whirlwind Start

It’s hard to believe that just seven weeks have passed since stepping into the role of President of the British Society of Paediatric Dentistry (BSPD). The pace has been extraordinary — a blend of international collaboration, national engagement and a deep sense of responsibility to represent our members, our profession and, most importantly, our patients.This period has been full of learning, reflection and gratitude. From my preparing for my first Executive meeting as Chair to representing the Society internationally, every moment has reminded me of the strength of our collective purpose: to improve the oral health and wellbeing of children everywhere.

Representing BSPD on the Global Stage

My first international engagement as President took me all the way to Cape Town for the 2025 International Association of Paediatric Dentistry (IAPD) Congress — my first official overseas representation of BSPD.

After my daughter’s last minute 36-hour hospital stay due to febrile neutropenia, I must admit I was very anxious about leaving her, especially for such a long period. Nevertheless, she thoughtfully suggested that the opportunity to represent our Society on the global stage was too important to miss. The warm reception, the diversity of voices, and the shared dedication to children’s oral health made it an unforgettable and worthwhile experience, despite my initial anxiety.

One of the most memorable days was joining Dr Linda Greenwall and the Dental Wellness Trust outreach programme in a township school. There, we saw the incredible work of the Toothbrushing Mamas — local women trained to deliver oral health education to children living in deprived circumstances. Their energy, music and spirit filled the hall; it was humbling and uplifting in equal measure.

Alongside BSPD colleagues and friends from around the world, a chance encounter with Judy Humphreys, Senior Lecturer & Honorary Consultant at the University of Liverpool, on the bus enroute to the outreach programme, made it feel like a home away from home. 😊

The next day, I proudly sat in the front row of the IAPD Council meeting, alongside Dr Joana Monteiro, a former colleague and consultant whom I had the pleasure of inviting, as BSPD’s representatives. It was a packed agenda, with the addition of new member societies joining the global paediatric dentistry community, voting on critical constitutional changes and learning that India will host the 2029 Congress (following Japan in 2027), which was especially meaningful for me as someone of Indian heritage.

Building Bridges and Sharing Perspectives

While in South Africa, I also reconnected with international colleagues and fellow Alumni from the Senior Dental Leaders (SDL) Programme (Harvard) that I had the immense pleasure of attending in 2023. This included Dr Jorge Castillo, Immediate Past President of IAPD (Peru) and Professor Veerasamy Yengopal, Dean of the University of the Western Cape Dental School, South Africa. Conversations over dinner explored the intersections between globalisation, education, and oral health equity — reinforcing that the issues we face in the UK are echoed worldwide.

A free walking tour through Cape Town provided a sobering reminder of the enduring effects of apartheid, yet also of the resilience and optimism that define South Africa’s people. It was a deeply grounding experience that strengthened my resolve to ensure our work at BSPD continues to champion inclusion and social justice in child health.

Driving Change at Home

Back in the UK, there’s been little time to rest. I’m delighted to share that I will be chairing a working group as BSPD President on behalf of the Office of the Chief Dental Officer (England) to update the NHS Clinical Standard for Paediatric Dentistry — a landmark opportunity to help shape national expectations for the delivery of paediatric dental care.

Equally exciting is our joint project with the Royal College of Paediatrics and Child Health (RCPCH) to develop a cross-disciplinary oral health toolkit for professionals. This co-produced resource aims to embed oral health within broader child health frameworks. Calls for expressions of interest to support both work streams will be shared with relevant stakeholders within paediatric dentistry in due course. Please keep an eye out for these communications.

I also want to extend heartfelt thanks to Dr Claudia Heggie and Dr Cheryl Somani, BSPD members who represented paediatric dentistry in updating the Royal College of Surgeons Guidelines, “The Oral and dental management of patients before, during and after cancer therapy 2025”. For the first time, this guidance includes a dedicated section focusing on the oral and dental health of children— a testament to their advocacy and expertise.

Celebrating Collaboration

As we continue to strengthen our policy voice, BSPD recently supported two important pieces of work:

• A policy briefing by the Children and Young People's Health Policy Influencing Group (HPIG), “Implementing the NHS 10 Year Plan”, where BSPD contributed as a key stakeholder, and

• The Antimicrobial Resistance Awareness Campaign, in anticipation of World Antimicrobial Awareness Week (WAAW), due to take place from November 18–24th.

These efforts reflect our growing presence as a credible and constructive partner in national policy discussions — an essential step as we move towards embedding oral health across all aspects of health and social care.

You may also have seen our recent advertisement for a Special Advisor – Policy & Strategy, a new consultancy role designed to support this growing area of work. Please do share within your networks — we’re seeking someone with strategic insight, political awareness and a passion for advocacy to help elevate our voice further.

An Invitation to Collaborate

At the heart of BSPD’s success lies our members. I want to harness your innovation, experience and enthusiasm to ensure our collective impact reaches those who need us most.

If you’ve developed a patient or professional resource for vulnerable or medically complex children — please get in touch (media@bspd.co.uk). Rather than reinventing the wheel, BSPD is keen to co-brand and help disseminate high-quality materials that could benefit a wider audience. This spirit of collaboration is central to our work — local innovations, shared nationally, can transform care for children across the UK.

Looking Ahead

As I prepare to chair my first BSPD Executive meeting as President later this month, I’m keen to hear your views. Which issues should we be prioritising? Where can BSPD better support you — locally, regionally or nationally?

This presidency is not about one person — it’s about all of us, working together to improve oral health for all children and young people. I look forward to continuing this journey with you — connecting ideas, strengthening partnerships and ensuring that every child, regardless of circumstances, can access the care they deserve.

Until next time, thank you for your continued dedication and support.

With warm wishes,

Oosh

Dr Urshla (Oosh) Devalia

President, British Society of Paediatric Dentistry

Photos L2R:

• Distributing oral health “goody bags” to Year 4 children at Nayameko Primary School

• With Dr Tshepiso Mfolo. President of the South African Association of Paediatric Dentistry

• Dr Jorge Castillo (Peru), Immediate Past President for IAPD and SDL Alumni

• Judy Humphrey’s supporting the outreach programme to Nayameko Primary School

• Toothbrushing Mamas

• Representing BSPD at IAPD Council alongside Dr Joana Monteiro

Unlocking the ORE: why the registration process to take the overseas registration examination should be made fairer

By: Dr Shannu Bhatia, Dr Prabhleen Anand and Dr Rohini Mohan

November 2025

Access to dental care in the United Kingdom has become a growing concern, with many regions experiencing severe shortages in NHS dental care, often referred to as “dental deserts.” This lack of access has had a detrimental impact on patients’ oral health, including that of children and has eroded public confidence in NHS dental services. It is therefore imperative that regulatory bodies and professional leadership take a strategic approach to assessing and addressing the workforce requirements within dentistry.

Overseas-qualified dentists have long been an integral part of the UK dental workforce. Over several decades, they have demonstrated their value through high-quality clinical service within the NHS, as well as through significant contributions to teaching, research, and leadership at national levels. Their inclusion strengthens both the profession and patient care, highlighting the importance of maintaining accessible pathways for overseas qualified dentists to apply for the Overseas Registration Examination (ORE) exam that would enable them to practice in the UK.

The ORE is a rigorous, robust and quality-assured examination designed to ensure that overseas-qualified dentists meet the high standards required for safe and effective practice in the UK. Having undertaken the predecessor to this examination (the IQE) and subsequently served as examiner, the authors can affirm the robustness and fairness of the assessment itself. However, the booking process for the exam presents a major challenge to candidates. Many candidates encounter repeated difficulties and frustration in securing a place to take the examination places despite multiple attempts, potentially discouraging and excluding practitioners who could make valuable contributions to the NHS. Improving the efficiency, transparency, and accessibility of the booking system is therefore essential.

Furthermore, the high financial burden associated with examination fees, the preparatory courses, and ongoing skills maintenance such as purchase of equipment creates additional barriers. In a society that values equality, diversity, and inclusion, it is vital to ensure fair access and support for all qualified professionals. Finally, efforts should also focus on making NHS careers more attractive—both for new graduates and overseas dentists—to promote retention and ensure a sustainable, skilled workforce capable of meeting the nation’s dental health needs.

You may wish to sign Dentistry.co.uk’s petition "Unlocking the ORE” which is campaigning to make the ORE registration process fairer.

Read more here: Unlocking the ORE

The Family Toothpaste: Supporting Simpler, Safer Oral Health for All Ages

Laura Warrilow – Specialist Paediatric Dentist – Birmingham Community Healthcare Trust

June 2025

Health visiting has a key role to play in empowering families to make informed, evidence-based decisions that support their baby/ child’s health and development. Oral health is no exception—but when it comes to something as seemingly simple as choosing toothpaste, many families are left confused by conflicting advice, marketing claims, and a wide variety of products on the shelves.

Toothpaste Confusion: What’s the Right Choice?

The Delivering Better Oral Health1 guidelines recommend different concentrations of fluoride toothpaste depending on a child’s age and their individual risk of tooth decay. In theory, this makes sense—tailoring fluoride levels can help balance the need for protection with safety considerations in young children.

This has led to uncertainty, both among practitioners and the families we support, about which toothpaste to recommend, when to switch concentrations, and how to ensure babies and children are receiving the right protection.

Family toothpaste: A Simpler, Safer Alternative

In response to this confusion, public health initiatives are increasingly supporting the use of a family toothpaste—a single fluoride concentration (1450 parts per million Sodium Fluoride) used by all members of the household. This approach prioritises clarity, consistency, and evidence-based protection against dental disease.

Rather than juggling multiple toothpaste tubes marketed for children of different ages and trying to decode packaging claims, families can use one product for everyone. This not only simplifies routines and reduces the chance of mistakes but also provides a tangible cost benefit—especially important at a time when many households are feeling the impact of the cost-of-living crisis.

By choosing a family toothpaste, families can confidently purchase lower-cost supermarket own brands or discount store options, knowing they are still providing optimum protection against tooth decay. This can significantly reduce the financial burden of buying multiple “age-appropriate” products, many of which are more expensive and not always better suited to children’s oral health needs.

Key Benefits of the Family Toothpaste Approach

There are several compelling reasons to consider recommending a family toothpaste:

• Cost-effective: Families don’t need to purchase different toothpastes for different ages, which makes managing household budgets easier and more sustainable.

• Reduces confusion: A single concentration eliminates the guesswork for both families and healthcare professionals about what is appropriate and when to change.

• Avoids marketing traps: Some children’s toothpastes display misleading age labels or feature cartoon characters that imply suitability without necessarily meeting evidence-based fluoride recommendations.

• Delivers optimum protection: A fluoride concentration of 1450ppm offers the best defence against dental decay for most individuals, regardless of age or risk level.

• Eases the taste transition: Babies and children become accustomed to the taste of adult toothpaste earlier, avoiding the sometimes difficult switch from milder or non-mint children’s toothpaste flavours as they grow.

Safety First: It’s About Quantity, Not Just Concentration

One of the most common concerns about using a higher-concentration toothpaste with younger children is the potential risk of fluorosis or toxicity from swallowing too much fluoride. However, it’s important to reassure parents that safety is primarily determined by the amount of toothpaste used—not just the concentration.

The Delivering Better Oral Health guidance remains clear:

• Children under 3 years should use a smear of toothpaste (Figure 1).

• Children aged 3–6 years should use a pea-sized amount (Figure 2).

• All children should be supervised when brushing.

Figure 1

Smear: up to 3 years

Figure 2

![]()

Pea-sized blob: 3 to 6 years

(Credit image: Delivering Better Oral Health: an evidence based toolkit for prevention).

By using the appropriate amount and encouraging children to spit (not rinse), families can feel confident that they’re supporting their child’s dental health safely and effectively.

Supporting Families Through Clear, Consistent Messaging

Through the universal reach of health visiting, practitioners are in a unique position to provide trusted, accessible advice to all families at a crucial time in their child’s development. Embracing the family toothpaste approach can reduce confusion, empower parents/carers, and ultimately improve oral health outcomes for the entire household.

Please promote this change through your work with families. This small change in recommendation could make a big difference—saving families time, money, and uncertainty while reinforcing our shared goal: healthy, happy smiles for every child.

________________________________________

Further Resources

1. Delivering Better Oral Health: An Evidence-Based Toolkit for Prevention

https://www.gov.uk/government/publications/delivering-better-oral-health-an-evidence-based-toolkit-for-prevention

2. British Society of Paediatric Dentistry – Brushing Advice

https://www.bspd.co.uk/Resources/Oral-Health-Resources

3. Institute of Health Visiting – Oral health resources and e-learning are avalible in the HWHN Toolkit which are free to members via iHV LEARN.

Beyond the clouds: The truth about vaping

By: Dr Vikash Patel, StR in Paediatric Dentistry, King’s College Hospital NHS Foundation Trust

Ms Maalini Patel, Consultant in Paediatric Dentistry, King’s College Hospital NHS Foundation Trust

Blog - May 2025

What is vaping?

Vaping is when someone uses a device, like an e-cigarette or vape pen, to inhale a mist or vapour.

These devices work by heating a solution (e-liquid) that typically contains nicotine, propylene glycol and/or vegetable glycerine (safe colourless liquids with a slightly sweet taste that are used in many foods and household items), and flavourings. It is possible to use an e-liquid that does not contain nicotine. Using an e-cigarette is called vaping and is not for children or young people. They are intended as a way for adults to stop smoking.

_________________________________________________________________________________________

Working within South East London, we have noticed an increase in the number of children and young people (CYP) vaping. There have been a handful of cases where clinical examination has revealed oral changes, which may be attributed to a vaping habit. In these CYP, white patches were noted, appearing as leukoplakia, similar to the appearance of smoker’s keratosis. For each case, oral medicine input was arranged along with a biopsy to rule out any dysplastic changes.

As a team we recognised we had a limited knowledge regarding the implications of vaping, we were not always asking every CYP about vaping habits, and we were unsure of what to advise when our patients disclosed that they did in fact vape.

We decided to make it a priority to ensure we were ‘Making Every Contact Count’ with regard to vaping by:

Asking every CYP about their vaping habit

• Training our team regarding vaping

• Ensuring we screen every CYP for oral changes as part of our examination

• Referring on all CYP with oral changes to our joint oral medicine paediatric clinic

• Educating our team about vaping cessation and where to signpost CYP for help

What is the legal position?

The legal age to buy a vape in the UK is 18

How does vaping affect the mouth?

As the prevalence of vaping in children and young people (CYP) is a relatively recent phenomenon, comprehensive long-term data regarding oral implications is unavailable.

Nevertheless, preliminary studies have identified potential complications:

• Oral dryness: vaping can reduce saliva production, leading to a drier mouth, which increases the risk of tooth decay.

• Mouth sores: vaping can irritate the delicate tissues of the mouth causing sores, white patches, chronic irritation, burning sensations and ulcers.

• Gum disease: some chemicals in vape aerosols change the balance of natural bacteria in the mouth, increasing the risk of gum disease.

• Tooth discoloration: nicotine and other chemicals in vapes can stain teeth over time.

• Tooth sensitivity: vape liquids contain acidic chemicals and flavourings which can erode tooth enamel over time.

• Oral Cancer: while the risk is lower when compared to tobacco smoking, some studies suggest a possible link between vaping and oral cancer. Longer term effects of vaping are still under review.

• Complications after dental procedures: vaping can affect the natural wound healing process in the mouth, and so patients should not vape before or after dental surgery.

• Increased risk of oral infections: with a reduced immune response in the oral cavity and presence of dry mouth, there is an increased risk of fungal infections like oral thrush.

• Slower orthodontic teeth movement: prolonged treatment duration and slower progress in aligning teeth is suspected, however longer-term studies are required to confirm.

What resources can we signpost to?

• Talk to Frank https://www.talktofrank.com/drug/vapes

• Youth Vaping: The Need to Know https://oursaferschools.co.uk/2024/09/17/youth-vaping-the-need-to-know/

• Action on smoking and health www.ash.org.uk

• General Medical Practitioners who can provide personalised advice, assess nicotine dependence, and recommend appropriate cessation strategies

What next?

The BSPD supports the implementation of stricter regulations on e-cigarettes, marketing, flavours and sales to minors in addition to investment in long term research.

At King’s, we are collaborating with our Paediatric Respiratory team to create information for CYP regarding the risks of vaping and how to access support.

Recommendations for Oral Healthcare Professionals Regarding Vaping Cessation

- Integrating questions about vaping into medical and social history forms

- Training the team regarding vaping. The National Centre for Smoking Cessation & Training (NCSCT) offer online resources for training.

- Development of local pathway for cessation. Teams should engage with their local smoking cessation pathway or paediatric respiratory teams regarding the availability of local resources. In the absence of established local pathways, referral to the patient's general medical practitioner for support regarding cessation.

- Screening for oral changes: Every CYP should undergo a full soft tissue examination and this is particularly important for those who disclose that they vape. Documentation can be supplemented by clinical photography, and biopsy should be considered.

The Hidden Dangers of Vaping for Children and Young People: A National Perspective

Dr Urshla (Oosh) Devalia, President-Elect for the British Society of Paediatric Dentistry

When Professor Warren Lenney reached out to me via our Royal College of Paediatrics and Child Health (RCPCH) network about the impact of vaping on children and young people (CYP), it reinforced something I had already been hearing from colleagues—this is a growing concern, and we need to act. As President Elect of the British Society of Paediatric Dentistry (BSPD), I was asked to contribute to the national conversation, ensuring oral health remains part of the wider health debate.

Vaping has crept into the lives of CYP at an alarming rate. It’s marketed as a safer alternative to smoking, but the reality is that we simply don’t know enough about its long-term effects, especially on developing bodies. What we do know is worrying—vaping exposes young users to harmful chemicals, leads to nicotine addiction, and is already showing potential links to gum disease, tooth decay, and oral lesions.

At BSPD, we’ve been clear in our stance: more research is urgently needed. However, while we wait for the data to catch up, we cannot sit back and do nothing. That’s why I provided a statement on behalf of BSPD to support the Tobacco and Vapes Bill, currently progressing through Parliament. Our position aligns with our respiratory colleagues—we support stricter regulations on vape marketing, flavours, and sales to minors. We also back investment into research that examines not just vaping’s impact on lungs but also its effects on oral and systemic health.

The Making Every Contact Count approach is crucial here. Whether in paediatrics, dentistry, or general practice, we must routinely ask CYP about vaping habits and provide clear guidance. We also need better referral pathways for oral health concerns linked to vaping—something that will require collaboration between dental, medical, and public health professionals.

As this debate continues, I remain committed to keeping oral health at the forefront of policymaking. Vaping is not a ‘harmless’ habit for CYP, and we have a duty to protect them. The more we understand, the better we can safeguard their future health.

New supervised toothbrushing programme for England – the government has now ‘put its money where its mouth is’!

By Peter Day, Zoe Marshman, British Society of Paediatric Dentistry (BSPD) members and Kara Gray-Burrows on behalf of the BRUSH team

31st March 2025

In an unprecedented commitment to improving children’s oral health, the government has delivered on its manifesto pledge and invested £11million, for the 2025-26 period, to support supervised toothbrushing programmes for children aged 3-5 years old living in the most deprived areas of England. Additionally, Colgate will provide 23 million toothbrushes and fluoride toothpaste to support both the supervised toothbrushing programme and at home brushing.1

The funding aims to support up to 600,000 children to undertake supervised toothbrushing. This figure identifies that supervised toothbrushing is a classroom activity and is targeted at early-years settings rather than at individual children. The additional funding will be given to local councils as part of their Public Health grant. Local authorities have statutory responsibilities for oral health promotion and can use established early-years networks to maximise uptake. The BRUSH research team has identified that 143,200 children are already taking part in these programmes. This figure has risen from 106,273 in 2022, but these figures include children of all ages and in both mainstream and special schools.2,3

What is supervised toothbrushing?

Supervised toothbrushing supplements home-based toothbrushing undertaken by parents and carers. In early-years settings (schools, nurseries or childminders) children brush their own teeth with fluoride toothpaste, with the activity overseen by early-years staff. The activity takes less than ten minutes and is undertaken at a convenient time as part of the daily timetable.

What is the evidence?

There is strong evidence from Scotland’s Childsmile programme that supervised toothbrushing reduces the prevalence of tooth decay and is cost-effective providing a £3 return on investment to the NHS for each £1 spent.4 Importantly, it reduces health inequalities with children from the most deprived backgrounds having the greatest benefit in the shortest time.5

There have been concerns that a national supervised toothbrushing programme would introduce a “nanny state” in that toothbrushing should be the sole responsibility of parents and such programmes place pressure on the education sector.

Indeed, the education sector is under significant pressure, but in the long-term such programmes may alleviate several health, social and educational issues. For example, oral health is now included in the early-years national curriculum and is a part of Ofsted inspections. Initial research has shown an association between lower levels of school readiness, attendance and dental caries.6,7 If a child is absent from their early-years setting they miss the benefits and opportunities that education can offer them.

There are lots of ‘myths’ circulating about children queuing for teachers to do the toothbrushing and schools needing to install loads of sinks. Excellent videos, like this one, demonstrate how quick and easy supervised toothbrushing can be. Endorsements from enthusiastic early-years staff and local dentists do really help.

We know that home brushing and parental supervision can be challenging despite many parents’ best intentions. Activities in early-years settings can provide much-needed daily exposure to fluoride to complement home-based toothbrushing and develop skills critical for long-term oral health. Most parents really appreciate the help with some lovely stories shared in this recent news item.

So yes, there is strong evidence that shows the effectiveness of supervised toothbrushing but to maximise children’s oral health it needs to be part of a wider package of measures as outlined in the recent ‘Child of the North’ oral health report.8

Where can I find out more information?

The BRUSH team based at the Universities of Leeds and Sheffield have undertaken a comprehensive programme of research to describe the current provision of supervised toothbrushing programmes across England and the barriers and facilitators to their implementation. They have produced an evidence-based toolkit, www.supervisedtoothbrushing.com, that has been accessed by over 15,000 visitors since its launch. It provides local authorities, oral health teams, early-years settings and parents with clear protocols, step-by-step guides and top tips.

How, as a BSPD member, can I support the national roll out? Winning hearts and minds in your local area

To find out more what is happening in your local area please contact your local dental public health consultant or the oral health team overseeing the programme. Maps, produced by the BRUSH team, show how many children and which areas are already undertaking supervised toothbrushing programmes.9

A key facilitator of implementation10 is advocacy and support from local ambassadors for children’s oral health whether it’s through supportive conversations at oral health steering group meetings (Local Dental Network and Managed Care Network meetings) or working with oral health teams with local early-years settings (primary schools, nurseries and childminders) to provide support where needed.

We welcome the national roll out of supervised toothbrushing as a key initiative of a wider multi-faceted strategy to achieve the government’s aim of raising the healthiest generation of children.

1. https://www.bspd.co.uk/Portals/0/Press%20Releases/2025/FINAL%20BSPD%20STB%20press%20release%207.3.25.pdf

2. Gray-Burrows KA, Day PF, El-Yousfi S, Lloyd E, Hudson K, Marshman Z. A national survey of supervised toothbrushing programmes in England. Br Dent J. 2023 Aug 21. https://www.nature.com/articles/s41415-023-6182-1

3. Broomhead T, Watt S, El-Yousfi S, Gray-Burrows KA, El Shuwihdi H, Hudson K, Day PF, Marshman Z. Supervised toothbrushing programmes in England: a national survey of current provision and factors influencing their implementation. Br Dent J. 2025 Jan 17. https://www.nature.com/articles/s41415-024-7782-0

4. Public Health England. Return on Investment of oral health improvement programmes for children aged 0-5 years old. 2016. https://assets.publishing.service.gov.uk/media/5a80ee0bed915d74e6231403/ROI_oral_health_interventions.pdf

5. BRUSH website – summary of evidence for supervised toothbrushing. https://www.supervisedtoothbrushing.com/1-4-evidence

6. Giles E, Relins S, Gray-Burrows K, Baker SR, Day PF. Dental caries and school readiness in 5-year-olds: A birth cohort data linkage study. Community Dent Oral Epidemiol. 2024 Oct;52(5):723-730. https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1111/cdoe.12968

7. Bond, C., Munford, L., Birks, D., Shobande, O., Denny, S., Hatton-Corcoran, S., Qualter, P., Wood, M. L., et al (2024). A country that works for all children and young people: An evidence- based plan for improving school attendance. See page 32. https://eprints.whiterose.ac.uk/219154/

8. Marshman, Z., Day, P. F., Wood, M. L. et al. (2024). A country that works for all children and young people: An evidence-based plan for improving children’s oral health with and through education settings, https://eprints.whiterose.ac.uk/217803/

9. BRUSH website – maps showing which local authorities and how many children are already involved in supervised toothbrushing programmes across England

https://www.supervisedtoothbrushing.com/1-5-1-2024-map-data

10. Gray-Burrows KA, El-Yousfi S, Hudson K, Watt S, Lloyd E, El Shuwihdi H, Broomhead T, Day PF, Marshman Z. Supervised Toothbrushing Programmes: Understanding Barriers and Facilitators to Implementation. Community Dent Oral Epidemiol. 2025 Jan 29. https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1111/cdoe.13026

My Journey with Ectodermal Dysplasia: From Patient to Paediatric Dentist in Training

By Leonie Watson, BDS

5

March 2025

A perfect smile is something everyone dreams of, but for me, the journey to achieving mine was quite different. At the age of two, I was diagnosed with Ectodermal Dysplasia, a condition that primarily affected my teeth, hair, sweat glands, and skin. Since my diagnosis, I was under the care of the specialist team at Bristol Dental Hospital and now at Newcastle Dental Hospital. I received my first set of dentures at 5, started orthodontic treatment at 12, and finally had dental implants placed at 22—an experience that not only transformed my smile but also gave me the confidence I had longed for. This treatment plan lasted a decade, through braces, and, towards the long-term goal of implants. These experiences played a huge role in shaping my passion for dentistry, and now, as a final-year dental student preparing for my foundation year, I can reflect on how my journey has influenced both my clinical knowledge and patient care.

A Unique Perspective: Patient and Dental Student

Going through my own dental treatment has put me in a unique position—both as a patient and as a dental student. My personal experience with implants has significantly shaped my understanding of complex dental procedures. This has helped me apply my knowledge in clinical practice with greater empathy and a deeper appreciation for what my patients may be going through. I don’t just approach implant dentistry as something I’ve learned about; I’ve lived it.

Early Memories at the Dentist

My visits to the dentist both at the hospital and local practice were always positive, largely due to the kindness and patience of my dental team. As a young child, my consultant affectionately called me “Miss Wrigglebottom” because I could never sit still in the chair, often treating it more like a slide than a seat! My dentists always found creative ways to keep me still, especially when taking impressions. Now, as a dental student, I use some of these same techniques when treating paediatric patients.

Although I enjoyed my visits to the dental hospital (partly because they meant missing school for the journey to Bristol), there were challenges. At school, I struggled when my friends talked about their wobbly teeth or excitedly shared stories of visits from the tooth fairy. I had no wobbly teeth, and I found it difficult to explain why. Sleepovers were also tricky—I would wake up before everyone else just to put my dentures in, worried about what my friends might think. My parents did everything they could to make things easier, sometimes even arranging surprise visits from the tooth fairy, despite there being no tooth under my pillow.

My Implant Journey

At eighteen, just as I sat my A levels, my implant journey began with a CBCT scan, which revealed that I needed a bone graft before placement. I received treatment at Newcastle Dental Hospital, where I underwent a bone graft and had four implants placed—two in my upper jaw and two in my lower. As a dental student, I found the process fascinating, especially the intricate planning required for each step. Experiencing multiple procedures, including two general anaesthetics and several restorative appointments, gave me first-hand insight into what it’s like to be on the receiving end of complex dental treatment. Despite the discomfort—especially from the stitches—I knew it was all worth it when I finally saw my perfect smile in the mirror.

Applying My Experience to Clinical Practice

Having been through extensive dental treatment myself, I can now apply my experiences to my own patient care. For example, when providing patients with dentures, I can truly empathise with their concerns and frustrations because I’ve been in their position. I understand the challenges of adapting to new prosthetics and the impact they can have on confidence. Additionally, I recently observed another patient undergoing the same implant procedure I had, which gave me a completely new perspective. Seeing the precision required by the dental team deepened my appreciation for the treatment I had received and reinforced the importance of careful planning and execution.

Looking Ahead

My journey with Ectodermal Dysplasia has not only shaped me as a person but also as a future dentist. The support and compassion I received from my dental team inspired me to pursue a career in paediatric dentistry, and I hope to provide the same level of care and empathy to my own patients. I know first-hand how life-changing dental treatment can be, and I am excited to use my experiences to help others—especially paediatric patients who may be facing similar challenges.

Dentistry has given me my smile, my confidence, and my career. I couldn’t ask for more.

See more information courtesy of The ED Society: My Implant Journey - The ED Society

CDS GIRFT: An Opportunity to Get It Right the First Time.

By Dr. Urshla (Oosh) Devalia

President Elect for the British Society of Paediatric Dentistry & Member of the CDS GIRFT Working Group

January 2025

As someone who has recently started to work with Community Dental Services (CDS) at a clinical and strategic level, I have come to understand firsthand how vital these services are for some of the most vulnerable members of our society. I was invited to be a member of the working group for the Getting It Right First Time (GIRFT) Community Dental Services Report and feel this to be a landmark moment—an opportunity to address long-standing disparities and finally raise the profile of CDS. But let’s be honest: making these recommendations work “in the real world” won’t happen without effort, collaboration, strong leadership and, in some areas, a fundamental shift in how we think about service delivery.

A System in Need of Change

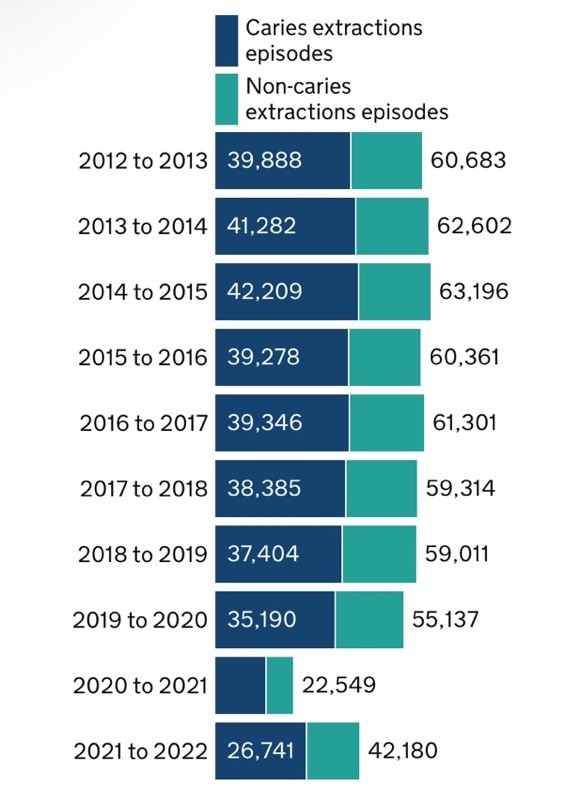

Why is this report so significant? For years, the CDS has been the safety net for patients who fall through the cracks of mainstream dental care—children requiring general anaesthesia for tooth extractions caused by preventable decay, adults with complex special needs, and those who face social or economic barriers to care. Yet the system that underpins these services has been fragmented, under-resourced, under-funded and inconsistently managed. The GIRFT report doesn’t just identify the problems; it offers a workable pathway to a more consistent, efficient, and equitable future for CDS.

Key Wins: Where the Opportunities Lie

The report highlights several areas that, if addressed properly, could be game changers for CDS.

1. Standardised Data Collection: For too long, locally held waiting lists have been invisible at a national level, leaving commissioners in the dark about the true scale of the problem. Establishing consistent national datasets is a no-brainer—it will bring transparency, enable benchmarking, and ensure resources go where they are needed the most.

2. Governance and Accountability: The call for formal Service Level Agreements (SLAs) between CDS and acute trusts will be critical. These agreements will create clearer lines of accountability, particularly for general anaesthetic services which are regularly cancelled as felt a low priority, in exchange for what are deemed to be “more important” services. This report will help ensure that standards of service delivery are consistent across the board.

3. Training and Workforce Development: CDS has untapped potential as a training ground for dental professionals. Investing in training posts will not only help to address workforce shortages, especially in rural and coastal areas, but also make CDS an attractive, sustainable career choice. This is a long-overdue step that could transform the workforce landscape.

4. Collaboration Through Shared Care Models: The push for stronger collaboration with Managed Clinical Networks (MCNs), Integrated Care Boards (ICBs), and primary care providers is another highlight. A shared care approach ensures that patients receive the right care, in the right place, at the right time—avoiding duplication and reducing pressure on secondary care services.

5. Focus on Prevention: Prevention has always been the holy grail of healthcare. By integrating health promotion into core CDS services, we can hope to reduce reliance on general anaesthesia and tackle dental disease at its root cause. This isn’t just good for patients—it’s cost-effective and aligned with the broader NHS strategy.

A Realistic Reflection: Where the Challenges Lie

While the recommendations are strong, implementing them won’t be easy. Establishing consistent national datasets may appear straightforward on paper, but this requires robust systems, training, and buy-in from all stakeholders. Without clear definitions and processes, we risk creating another layer of bureaucracy without improving outcomes. Similarly, while investing in training is critical, it will take time to see the benefits. In the short term, workforce shortages will remain a challenge, and services will need support to manage increased demand.

Additionally, many CDS services already operate on underfunded budgets, so whilst the reports’ recommendations are sensible, they require investment, and we need to ensure funding is available to implement these changes without compromising existing services. Finally, while preventative care is noted as a key-win in the report, embedding it into the core of CDS service delivery demands both cultural and operational shift as prevention often takes a backseat to immediate clinical priorities. Addressing these challenges thoughtfully will be key to the report's success and real-world applicability.

Looking Ahead

The GIRFT report represents a golden opportunity to transform CDS—but success depends on all of us. Commissioners, clinicians, policymakers, local leadership and service users must come together to make this vision a reality. There will be challenges, but the potential rewards—healthier communities, better patient experiences, and more sustainable services—are well worth the effort.

To formally explore the CDS GIRFT recommendations, I encourage you to join the upcoming webinar:

Community Dental Services – Reducing Variation to Improve Dental Care for the Most Vulnerable

📅 Date: 29 January 2025

🕒 Time: 12:30pm – 1:30pm

🔗

Register Here

This is our moment to get it right for CDS, even if it’s not the first time!

MY THOUGHTS ON ATTENDING THE 3rd IAPD GLOBAL SUMMIT

DR SHANNU BHATIA, PRESIDENT, BSPD

January 2025

I was delighted to represent BSPD at the 3rd IAPD (International Association of Paediatric Dentistry) Global Summit: Pulp Therapy Rooted in Evidence which was held between November 8-10, 2024 in the beautiful city of Porto in Portugal.

The summit saw leading clinician scientists from across the globe gather to explore and share the latest developments in pulp therapies for children and young people. Expertise from across the world shared advancements in our understanding of pulp biology, the inflammatory response to dental caries and trauma, as well as innovations in diagnosis and pulp treatment. I fully appreciated the value of what a unique opportunity it was to connect with professionals at the very forefront of paediatric dentistry research and development – which allows me to bring back knowledge that can benefit practice. Renowned experts Yasmi Crystal, James Coll, Anne O’Connell, Nicola Innes and Jonas Rodrigues shared cutting-edge research on effective pulp management of primary and permanent teeth affected by deep caries or trauma.

During the three day conference, I was invited to attend the Association Leadership workshop led by John S Rutkauskas which was particularly stand-out in terms of the insights and practical take-away messages. We learnt about value-based leadership, with its emphasis on core values like reflection, balance, humility, accountability, clarity, and empowerment. These are excellent approaches for organisations focused on healthcare, where the ultimate goal is to make a difference in patient outcomes. By aligning leadership practices with these principles, paediatric dentistry can foster stronger teams, more transparent decision-making, and long-term ensure a more collaborative and sustainable impact.

The topic of good management and ultimately the wellbeing of the dental workforce are subjects of particular interest to me, since I have focused much of my research time recently - back at the School of Dentistry at Cardiff University, where I am the lead for Paediatric Dentistry - on this important subject. What my own investigations have shown me is that whilst appropriate patient care is of course fundamental, this must be considered alongside ensuring the mental and physical well-being of trainees and staff who are tomorrow’s dentists. So, I was heartened to see a focus in a global forum on the importance of the working environment for the dental team.

Further discussions provided valuable strategies for managing the challenges specific to paediatric dentistry, particularly as it relates to improving the oral health of children on a broader scale, with the importance on the most vulnerable paediatric patients being a focus. This an area of particular importance for us in the UK, so again it was interesting to see this engagement on a wider level.

Overall, the conference felt well-rounded with its focus on up-to-date research on managing carious teeth in young people. Having international speakers share insights on current evidence-based practices undoubtedly enriched the experience, giving attendees practical knowledge to enhance care within their own communities.

I was able to meet with Paediatric Dentists from a myriad of other organisations, including Dr Figen Seymen, the current President and Dr. Soni Stephen, the President-Elect of IAPD, to discuss the common values we all share.

International conferences to share global insights and experience provide a valuable exercise in sharing best practice and the latest learnings, so it was heartening to see the engagement from the large number of attendees in Portugal this year.

ATTENDING THE CHIEF DENTAL OFFICER’S ROUND TABLE: INSIGHTS ON THE FUTURE OF DENTISTRY

DR SHANNU BHATIA, PRESIDENT, BSPD

SEPTEMBER 2024

Recently, I had the opportunity to attend the Office of the Chief Dental Officer’s (OCDO) Round Table event, as BSPD President where I engaged with leaders from various specialties and key stakeholders in the dental field. The event provided a unique platform for updates, policy discussions, and collaboration on the pressing issues facing dentistry in the UK.

The CDO, along with other policy makers, delivered insightful updates that sparked engaging discussions. Notably, Navina Evans, Chief Workforce training & education officer for NHSE, shared updates on workforce development. Dominic Robson, Senior Policy Manager, Dentistry, and Jane Luker, Postgraduate Dental Dean and Chair of the English Dental Deans, also contributed with thought-provoking presentations on policy and training pathways.

Round table discussions centred on critical topics like dental disease prevention, workforce retention, and supporting trainees in the field. I know from my own experience and research just how important focusing on the wellbeing of the dental workforce is in terms of helping with retention and shoring-up the dentistry workforce for the future. BSPD’s ‘Right Care at the Right Time’ theme at our recent conference expounded on this understanding – ie: that caring for the patients is of course our focus, but to do that we must support the dental teams to deliver the best care.

Paediatric dentistry also took a spotlight moment at the round-table, with a strong emphasis on the importance of prevention for the youngest in our society. Public health campaigns promoting preventive care, along with initiatives like community water fluoridation (CWF), were suggested as essential steps forward. We also know the positive impact to patients’ oral health - and the NHS purse – initiatives such as targeted supervised toothbrushing can have. These campaigns are working effectively in the devolved nations (Scotland – and back in my home nation, Wales), as well as being carried out with good results in some areas in England. Rolling targeted supervised toothbrushing out in England should be a priority and we need to hold the new government to account on this, since it was one of their manifesto pledges pre-election.

This OCDO round-table meeting highlighted the importance of collaboration across specialties and the need for proactive public health measures to improve oral health outcomes for the future. I look forward to seeing the actions discussed implemented, and meeting again with the group at the next round-table in the near future.

With dentistry currently in crisis, only continued collaboration, vision and on-going pressure can bring the much needed changes so badly needed.

The Looked After Children Oral Health Toolkit – a vital resource to help identify and support the oral health needs of children who often experience greater dental care needs

By Julia Hurry, Academic Clinical Fellow (ST1) in Paediatric Dentistry at Queen Mary University of London and Barts Health NHS Trust & General Dental Practitioner at 2 Green Dental

June 2024

Last month the “Looked After Children (LAC) Oral Health Toolkit” was published on the British Society of Paediatric Dentistry (BSPD) website. It is now available as a helpful resource to support those working with LAC including Integrated Care Boards (ICBs), Integrated Care Systems (ICSs) and dental care professionals. This guidance document was written by a group of dedicated experts in the field who shared the joint aim of broadening awareness of the specific oral health needs and challenges facing LAC in the UK.

The number of LAC in England rose to 83,840 in 2023 - an increase of 2% - continuing the rise seen in recent years both in England and the rest of the UK. This is a rate of 71 LAC per 10,000 children with regional variation across England. Most LAC are in foster placements (68%), where an approved carer looks after the child. LAC can experience high instability of placement with one in ten having 3 or more placements within 1 year. This high frequency of placement movement can make the continuity of dental care exceptionally challenging.

Local authorities have a statutory duty to arrange an initial health assessment, including a dental check, for LAC within 20 working days of a child being taken into care. Review health assessments occur every 6-months (for children <5 years) or 12-months (for children >5-years). Dental check-ups are monitored by local authorities; however, they are only reported for children who have been in care for at least 12-months and do not specify that young children must have their teeth checked by a dentist. This makes it more challenging to understand the true oral health needs of LAC.

There is little known about the oral health needs of LAC. A recent scoping review found that LAC had poor oral health outcomes and unmet needs including tooth decay, dental trauma, gum disease, pain and crooked teeth. These were thought to be possible consequences of entering care with untreated dental disease and/or lacking established oral health routines including low sugar diet and toothbrushing. However, as most of the data was accrued from LAC already accessing care, this is likely to only be the tip of the iceberg.

Four existing dental care pathways were identified within England for LAC by the scoping review, and it recognised the need for better integrated working between professionals involved in the care of LAC.

The Looked After Children Oral Health Toolkit aims to support ICBs, ICSs and key stakeholders in LAC oral health to identify their oral health needs and to help plan and deliver dental services for LAC. It is an easy-to-use guidance document which provides six key questions that ICBs can use to plan their dental services.

The Toolkit also provides examples of key organisations and partners as well as the roles that each of these bodies may take on to support the oral health of LAC and care leavers.

The Toolkit has embedded personal reflections and case studies from real-life examples of current activities and programmes in use across the UK, making the document feel relevant and achievable. The reflections and case studies provide further details of where these activities are taking place to encourage collaboration with the shared aim of improving the oral health of LAC. Support and resources available for professionals, foster carers and LAC themselves as well as a summary table of policy drivers and NHS initiatives can be found towards the end of the document.

The Looked After Children Oral Health Toolkit is a helpful guidance document for all those engaged in caring for LAC as well as LAC and care leavers themselves. It helps clarify the roles of key organisations and stakeholders, summarise policy drivers and NHS initiatives, collate useful resources, and provide real-life examples of current activities and programmes in the UK.

The authors hope this supportive document can be used to identify the oral health needs for LAC in their area and allow key organisations to plan and deliver dental services for an increasing cohort of children and young people who are known to face additional barriers in accessing dental care and have greater dental care needs. I hope that the Toolkit will help to make a real difference in the quality of life of a particularly vulnerable group of children, and will provide clear guidance to identify, address and monitor the oral health needs of LAC so that we can start to see an improvement in their oral health outcomes.

References:

Children looked after in England including adoptions. 2023. GOV.UK. Available at: https://explore-education-statistics.service.gov.uk/find-statistics/children-looked-after-in-england-including-adoptions (accessed 17/05/2024).

Hurry KJ, Ridsdale L, Davies J, Muirhead VE. The Dental Health of Looked After Children in the UK and Dental Care Pathways: A Scoping Review. Community Dent Health. 2023 Aug 31;40(3):154-161. doi: 10.1922/ CDH_00252Hurry08. PMID: 37162290.

Putting the fluoridation ball in the net…

By Simon Hearnshaw

Coordinator National Community Fluoridation network

April 2024

BSPD is a founder member of our community water fluoridation (CWF) network. Set up in 2016 working closely with the British Fluoridation Society, the network’s role is to raise the profile of fluoridation and work with a range of organisations with similar views on the importance of prevention and the effectiveness of the public health measure. BSPD has been key to the work that the network does because of the improved child oral health and reductions in exposure to GA extractions that fluoridation can bring. BSPD members have been instrumental in working locally and across organisational boundaries with groups like RCPCH. Elizabeth O’Sullivan has worked closely with the network in Hull and helped us get consideration of fluoridation included in the Starting Well Programme way back in 2017, and BSPD was amongst the first to publish a Position Statement (updated in October 2021) on CWF. There have been a lot of small steps along the fluoridation road, and now we are approaching the leap forward that we all want to see in the interests of the communities we work within.

Health & Care Act 2022 – taking fluoridation out of the ‘too hard box’

For many years it has felt like CWF has been put in the ‘too hard box’. Certainly, that’s what it felt like in the early days of the network. The Health and Care Act 2022 changes this, giving the Secretary of State the power to directly introduce, vary or terminate water fluoridation schemes. This removes the burden from local authorities effectively taking politics out of decision making and making this all about health and health equity. Now we have arrived at the first public consultation on CWF since 2008 with it the possibility of the first wholly new scheme since 1985. I qualified in December 1984, so this is quite literally a generational opportunity to make a difference.

Supporting the Public Consultation.

The Government is consulting on plans to expand community water fluoridation schemes across the north east of England. This area was chosen because of the poor oral health and inequalities in the region, and because the Local Authorities have all worked together over many years to achieve this goal for the communities they serve.

The consultation must take into consideration the extent of support for the proposal, the cogency of the statements made and the areas that are being represented in the responses.

Everyone can submit a response and all MCNs, LDCs should be encouraged to do this. However, submissions from the North East will be weighted. So, whilst it is important that we all get involved, it is critical that BSPD members in the North East do so.

Cogency is around the strength of the arguments put forward so these need to be based around the evidence base and professional lived experience.

The Evidence Base is extensive, but the key messages are:

CWF is effective.

CWF is safe.

CWF reduces inequalities.

CWF is cost effective.

CWF is sustainable.

The North East Water Fluoridation briefing has been produced by Kamini Shah and BSPD’s very own Chris Vernazza to support consultation responses. It contains a summary of the evidence base including cost effectiveness and local epidemiology data describing the local oral health need and impact of CWF.

More information can be found on the consultation site, in the recent dental update series on fluoridation, and the webinar from 2022.

Professional experience

International reviews and papers clearly contribute to the strong evidence base around CWF described in the position statement by the four UK CMOs. However, our professional lived experience is also convincing. Describing seeing the benefits of fluoridation, the impact of poor oral health, having to extract children’s teeth on a daily basis and admit children to hospital for a GA exodontia are powerful statements that add to the argument that communities need fluoridation as the only universal prevention intervention that requires no behaviour change and helps those that need help the most.

Please find the consultation here and take care to respond by the deadline of June 17th. Between us all we can ensure it is our generation of clinicians who put the evidence–based fluoridation ball in the net for the communities and in particular the children we serve.

The Newcastle BSPD conference through the lens of a recent graduate.

By Bethany Allan, BDS, Newcastle University Graduate 2023

I attended the BSPD conference in September this year as a recent graduate of the Bachelor of Dental Surgery degree. Paediatric Dentistry is something which I have grown to enjoy throughout dental school and certainly within the few months of starting my foundation year. My experience so far treating paediatric patients has made me appreciate the difficulty in providing high quality dental treatment. Alongside the complexity of the treatment itself, there are additional requirements such as ensuring that the parent is engaged and educated, behaviour management and verbal and non-verbal communication styles - to name a few. Therefore, I attended the BSPD conference to gain further insight on how to manage this patient group and explore the potential career options available within this field of dentistry.

On arrival, we were greeted by a busy trade fair full of enthusiastic company reps and even more enthusiastic paediatric dentists! I was immediately struck by the lively atmosphere, made clear by the swirling noise of old colleagues conversing and new colleagues connecting. We started the morning session in the lecture theatre where we were treated to a series of presentations looking at caries and how we combat health inequalities. The first presentation was delivered by Prof. Yasmi Crystal followed by Dr Sarah Sowden and Dr Sameena Hassan who delivered the second talk. I thoroughly enjoyed the first two presentations of the morning session, I thought the speakers were extremely knowledgeable in their field of dentistry and very informative, providing me with ideas which I could adopt within my own practice.

Prof. Yasmi Crystal

Lunchtime came, which provided a useful opportunity to explore further all that the trade fair had to offer. It was beneficial to gain further insight into the most recent products, materials, and technology used within dentistry. It is clear to see these companies are fully embracing preventative dentistry in Paediatrics. It was useful to take samples away which I have then been able to use with my own patients. The lunch break also provided an opportunity to catch up with my former university supervisors. As a recent Newcastle University graduate, it was great to see members of staff present at the conference who I had the privilege of being taught by throughout dental school. Being in the presence of such individuals, who are highly regarded in this field of dentistry, made me appreciate the level of experience, education and knowledge that was provided to me throughout my university years.

Following lunch, the afternoon session comprised a series of presentations from core trainees and registrars within Paediatric Dentistry. There was a mix of clinical cases and clinical governance-based discussions where the presenters gave insight into the projects that are happening within the different dental hospitals and their departments. Despite these presentations being very informative, some of the ideas discussed were more specialised than I would be able to utilise in my own clinical practice as a general dentist, as they were better applied to a hospital setting.

Prof. Hal Duncan delivered the last presentation about deep caries management and vital pulp therapies. I thoroughly enjoyed this presentation, there was lots of interesting and very useful content delivered in a relaxed and engaging style. Vital pulp therapy in paediatric dentistry was something I was not very knowledgeable and confident in, so this was one of the most useful aspects of the conference for me.

Generally, the day was very well organised with the social media presence helping to inform me of the proceedings throughout the day. I thought the venue was appropriate for the type of conference, however, a lecture theatre which was entered from the rear would have been less distracting as those entering the lecture theatre would not have to cross in front of the presenter.

This BSPD conference has not only been beneficial in terms of gaining better insight into the field of Paediatric Dentistry but also for networking with an array of different individuals who are also inspired and motivated to provide high quality care to this patient group. I found it very inspiring to hear of the hard work and determination of each speaker, which has ultimately led to the improvement of services provided to paediatric patients. As a dental student, I found Paediatric Dentistry particularly challenging, but the hints and tips I gained from the conference speakers has changed my opinion significantly. I have now applied multiple aspects into my current practice, and I would recommend this conference to any new graduate colleagues.

Why targeted supervised toothbrushing is the smart, yet simple approach for equitable children’s oral health.

By Professor Paula Waterhouse

October 2023

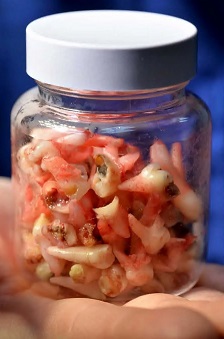

Consultant in Paediatric Dentistry, Claire Stevens holding jar of teeth extracted in one day at University Dental Hospital of Manchester . 13.09.17

Last week colleagues at the British Society of Paediatric Dentistry and I sighed with collective relief when, after over ten years of calling for supervised toothbrushing in England, the Labour Party announced a scheme to target three to five year olds in the twenty percent most deprived areas in England (based on the CORE20 part of the CORE20PLUS5 CYP1 initiative.

There is evidence, from Scotland that reaching children as early as possible with supervised toothbrushing schemes gives them a better oral health start to life and is more cost effective in the long term for the NHS.

Our Society’s team of spokespeople had a busy day once the announcement broke on Friday allowing us to explain to broadcasters and the press how this simple intervention, that is already happening in Scotland and Wales need only take a few minutes out of a school day. The debates ran all day with lively challenges from some who rightly aired concerns about teachers’ precious time being stretched – yet again. But the reality is, which we heard from a headteacher at a school in Bolton on Nicky Campbell’s BBC Radio 5 Live phone in, that it takes a sum total of 7 minutes after their lunchbreak to get all the 3-5 year olds brushing enthusiastically together – overseen by a teacher or assistant. The reality is that in this cost of living and NHS dentistry crisis, children’s oral health is everyone’s business.

This costed and funded proposal would see children attending schools and nurseries in areas of socioeconomic deprivation who receive supervised toothbrushing, also getting a supply of toothbrushes and toothpaste to take home. Additional investment has also been announced, increasing the number of children who should be able to see an NHS dentist. This is a serious plan to grip both the immediate crisis and set NHS dentistry on the path to recovery in the long-term. In an ideal world, BSPD believes that every child should have a ‘dental home’ – an ongoing and preventively-focused relationship with an NHS dentist. However, in the meantime we must recognise that, through no fault of their own, some children need greater help to get the oral health start in life that every child deserves.

We have heard of five year olds who have never seen a toothbrush before. We know of teenagers who have never been to the dentist. This is not OK. We want to put an end to stories like these. Some children, through no fault of their own, are not getting the oral health start that would set them up for life. This targeted approach will make a big difference and because the children get to take their toothbrushes and toothpaste home, this is about partnering with parents to ensure every child has a smile for life.

We therefore welcome these measures as we know we need urgent action to address the persistent and immoral inequalities we see in children’s oral health. Intervening with a targeted supervised toothbrushing scheme is proven to deliver beneficial oral health outcomes that also pay for themselves severalfold in the future.

Children and young people from lower socioeconomic groups are more likely to experience dental decay and more likely to report that their poor oral health impacts on their daily lives. These children can suffer pain, lose sleep and miss days at school. Dental disease is almost always preventable. This approach, that is based on targeting the most deprived 20% of children, is a step towards an oral health approach that is equitable – not just equal.

FDS RCS England Guideline for the Extraction of First Permanent Molars in Children

By Dr. Greig D. Taylor and Prof. Paul Ashley

July 2023

Care for children and young people presenting with compromised first permanent molars (cFPM) of uncertain prognosis, where either restoration or extraction are valid treatment approaches, can be difficult to plan. In these cases where cFPM are of uncertain prognosis, consideration and inclusion of other patient and tooth-related factors are needed to support the decision-making process (Ashley and Noar, 2019, Somani et al., 2021). We would like to promote that children and young people are an integral part in a shared decision-making process. Until recently, it was common these views were either not obtained, or valued by clinicians, when healthcare decisions were made. Personally, we feel this contradicts children and young people’s rights. They should have the right to assert their autonomy and their views, and as clinicians we should be prepared to listen to them.

In March 2023, the Royal College of Surgeons of England published an update to their 2014 ‘Guideline for the Extraction of First Permanent Molars in Children’ to help support these management decisions (Noar et al., 2023). Several changes have been made to this updated version, mainly to reflect the current available evidence, but also to highlight the importance of shared decision-making with the child, parents/guardians, and dental professionals (Ashley and Noar, 2019, Taylor et al., 2019, Somani et al., 2021, Noar et al., 2023).

Previous versions of the guideline have focused on removal of the cFPM at the time when the bifurcation of the second permanent molar was calcifying as this was believed to be the main predictor of successful closure, particularly in the lower arch. Identifying this feature remains in the updated guideline; however, it is not relied upon as the sole predictor as several others have since been identified. Factors such as presence/absence of third permanent molar and angulation of the second permanent molar are now important to ascertain when determining the likelihood of successful closure. Indeed, the presence of a third permanent molar and a mesially angulated second permanent molar, combined, are high positive indicators of successful closure (Patel et al., 2017). This highlights the need for a full radiographic assessment to observe such features and then rely on this information during the decision-making process.